Get your mind out of the gutter—I’m not that type of girl!

Paul Muni plays James Allen, a returning WWI GI who finds unemployment and then is unjustly convicted of theft and sent to a southern prison to serve on a chain gang, in this classic 1932 film directed by Mervyn LeRoy. One of Warner Bros. social conscience films, and the recipient of three Academy Award nominations (Best Picture, Best Actor (Muni), and Best Sound), the film depicts the harsh world of the southern penal system in the 1920s. Based on the autobiographical story of Robert E. Burns, a man who became a fugitive from a Georgia chain gang, this is an excellent indictment of an abusive prison system.

When James Allen returns home from the Great War he wants to do more than go back to his clerk job in a shoe factory. Instead he wants to go to engineering school so he can build bridges. The problem is his mother (Louise Carter) and his reverend brother (Hale Hamilton) want him to stay at Mr. Parker’s (Reginald Barlow) shoe factory and pick up where he left off before the war. Not the arguing kind, he finds himself back at that factory, but is distracted by a bridge being built outside his office window and he decides to head north to find construction work. This sets him off on a transient existence, moving from place to place looking for work. Things become so bad that he tries to pawn his war medals to no avail; the owner already has a drawer full—a nod to the dire circumstances that war veterans faced at that time.

Eventually he finds himself back in the South and ends up meeting Pete (Preston Foster), the man who will fatefully change his life forever. When they go to a diner for hamburgers, Pete pulls a gun and orders a bewildered Allen to take the money from the till (a whopping $5). When the police arrive they kill Pete and assume Allen was his accomplice. He is convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to ten years of hard labor.

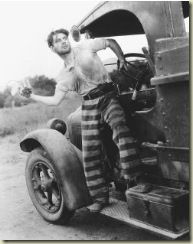

After seven months of relentless work on the chain gang, Allen decides to escape. He has a fellow prisoner bend his shackles so he can slide it off his foot and he borrows $7 and the address of a former inmate from another. While taking a bathroom break in the bushes, Allen slips off his shackles and sets off for freedom. He exchanges his prison clothes for some hanging on a clothesline and uses the swamp to evade the bloodhounds. In an often imitated scene, Allen uses a hollow reed to breathe underwater while guards and digs pass by.

Allen ends up in Booneville and meets up with Barney, a former inmate who gives him a place to sleep for the night. The next day while he is waiting for a train he orders a hamburger (evidently bad luck for him) and hears that the police are looking for the escaped prisoner. In a near-miss episode, Allen finds himself scrambling onto a train as the police point in his direction but run past him for another man.

Free, Allen journeys to Chicago, where he gets a job (under an alias) at the Tri-State Engineering Company and works his way up the company ladder. He ends up boarding with a scheming landlady, Marie (Glenda Farrell),

After years of hard work and study, Allen become a field superintendent and falls in love with Helen (Helen Vinson). Yet, he can’t get rid of Marie, who doesn’t care that he loves another woman. When he threatens her with a divorce she turns him in and he is arrested. His friends and the newspapers try to block his extradition to the South, especially after he describes how horrible the chain gang is. This causes a min-civil war between the northern and southern justice systems. Finally, Allen agrees to return to the prison for ninety days to work as a clerk, where thereafter he would be given a full pardon.

Once back in prison, Allen soon learns that this agreement won’t be kept by the Tuttle County Prison Camp. Instead, he is assigned to even harsher chain gang than before. After 90 days, his pardon hearing reveals that the state is angry with his public criticisms of their justice system and his pardon is denied but he is given the option of parole in nine months. Allen resigns himself to this nine month fate and is a model prisoner. Yet, when his case comes up

This is the granddaddy of prison-break films. When you watch Cool Hand Luke, The Defiant Ones, or O Brother Where Art Thou?, you are watching films inspired by this one. It unapologetically exposed the horror of a system of forced labor in the South, which ground men down into nothing or into their graves. It angered southerners so much that it was actually banned in Georgia—where the real-life story of Robert E. Burns took place.

Paul Muni is excellent as a man who wants nothing more than to be a productive member of society. He always had the ability to encompass the true nature of all the characters he played, whether it be an escaped convict or Prime Minister Disraeli. In addition, the maliciousness of Glenda Farrell as Marie is something to watch.

A classic prison break film and one of Muni’s best performances.

Kim, although I like Paul Muni, I was slow in seeking out this film. But when it came in a boxed set of CONTROVERSIAL CLASSICS, I watched it, of course...and was amazed at how gripping it was. As you pointed out, the closing scene (and dialogue) is unforgettable.

ReplyDeleteOf the Muni films I have seen this is by far the best. I liked it better than the Zola movie. In this one he us very believable. This is not a movie about toughened up gangsters, hi ordinary people caught in the system. A brave and relevant movie in 1932.

ReplyDeleteMuni is a bit of an over-actor for my taste, but I will agree that he is more believable here than in Zola. Have you seen him in Disraeli...oh, my.

ReplyDelete