(This article is from guest contributor Rick29 and first appeared at http://classic-film-tv.blogspot.com/. The rating in the title is my own.)

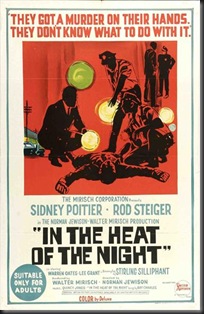

This racially-charged mystery, 1968’s Oscar winner for Best Picture, has aged gracefully over the years. The secret to its success can be attributed to its many layers. Peel back the mystery plot and you have a potent examination of racial tension in the South in the 1960s. Peel that back and you have a rich character study of two lonely police detectives, from completely different backgrounds, who gradually earn each other’s respect.

The film opens with a nighttime “tour” of Sparta, Mississippi, as police officer Sam Woods (Warren Oates) makes his rounds in his patrol car. He stops at a diner for a cold Coca Cola, then drives past closed shops with their bright neon signs. He pauses at a house where a young exhibitionist walks around in the nude. It’s a typical night in the sleepy little town…until Sam finds a dead body in an alley way.

The murder victim turns out to be an industrialist who planned to build a big factory in Sparta. The local police chief, Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger), quickly launches an investigation that results in the arrest of a well-dressed black man at the train station. Much to Gillespie’s dismay, he learns his prime suspect is actually a police detective from Philadelphia named Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier), who was awaiting a connecting train to Memphis. Tibb’s Philly superior tells Gillespie that Virgil is his “number one homicide expert.”

Though Gillespie doesn’t like Tibbs, he realizes that he needs help. Gillespie knows his subordinates are ineffective (they can’t even remember to oil the air conditioner) and the mayor won’t support him if he fails to find the killer quickly. Most importantly, Gillespie realizes that he’s out of his element; he just wants to run a “nice clean town” and lacks the expertise to handle a homicide investigation. For his part, Tibbs is torn—he’s eager to leave, but wouldn’t mind showing up these prejudiced, ignorant white men.

The film’s most famous scene is the confrontation between Tibbs and Endicott (Larry Gates), a wealthy cotton farmer and a principal murder suspect. Their conversation begins as a calm discussion on orchids, but Endicott quickly shows his racist side when he notes his flowers are “like the Negro…they need care and feeding and cultivating.” Tibbs coolly ignores the insult and persists with probing questions. When Endicott realizes he’s under investigation for murder, he slaps Tibbs across the face. Without hesitation, Tibbs strikes him back. When an enraged Endicott asks Gillespie what he’s going to do about Tibbs’ actions, the police chief replies simply: “I don’t know.”

Seen today, the scene still works as powerful drama. It no doubt had a greater and more significant impact when In the Heat of the Night was originally released. Ironically, Tibbs’ slap wasn’t in the novel nor the original screenplay (in both, Tibbs just walks away). In a February 2009 interview with the American Academy of Achievement, Poitier said he read the script and then told producer Walter Mirisch: “I will insist that I respond to this man (Endicott) precisely as a human being would ordinarily respond to this man. And he pops me, and I'll pop him right back. And I said, if you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. And in writing you will also say that if this picture plays the South, that that scene is never, ever removed.” Mirisch agreed and a classic, landmark scene made its way into a mainstream Hollywood film.

Historical significance aside, the film’s best-played scene has Tibbs and Gillespie relaxing in the latter’s drab home as a train whistle echoes in the distance. Drinking warm bourbon, Gillespie confesses to Tibbs that the Philly detective is the first person to see the inside of his home. Then, in an unguarded moment, Gillespie opens up about his mundane existence and isolation.

Gillespie: Don’t you get just a little lonely?

Tibbs: No lonelier than you, man.

Gillespie: Oh now, don’t get smart, Black boy. I don’t need it. No pity, thank you. No thank you.

The scene perfectly illustrates the performers’ contrasting acting styles (which is one reason why they work so well together). Steiger dramatically transforms from a sad sack looking off into a corner of room into a proud man who is offended that Tibbs would empathize with him. Poitier, meanwhile, says very little, slumping in his chair to convey exhaustion and leaning forward attentively to show interest in Gillespie.

Thanks in part to Stirling Silliphant’s excellent dialogue, In the Heat of the Night provides an ideal showcase for its two leads. Steiger, who had a tendency to overact in later movies, remains in total control here. Gillespie’s sloppy appearance, yellow-tinted sunglasses, and constant gum-chewing makes him look like a typical redneck Southern sheriff—but Steiger skillfully avoids playing the stereotype. Gillespie comes across as wily, independent, proud, prejudiced, and lonely. The performance earned Steiger a well-deserved Best Actor Oscar.

Poitier matches him scene for scene as the intelligent, proud, equally prejudiced Tibbs. He skillfully underplays the Philadelphia detective, so that when Tibbs strikes Endicott or flashes his anger toward Gillespie, those scenes catch fire. Amazingly, Poitier was not Oscar nominated, perhaps because his votes were split among three memorable 1967 performances: In the Heat of the Night, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and To Sir, With Love.

Strip away its atmospheric setting and riveting characters and In the Heat of the Night is just an average mystery. But, in this case, the plot is just a means to the ends. The film is foremost a character study of two strong-willed men (played by two actors at the peak of their careers). Secondly, it’s a portrait of Southern life in the late 1960s. Some of it may be exaggerated, but overall, screenwriter Silliphant and director Norman Jewison skillfully capture a time and a place—making the viewer feel like they’ve just experienced a visit to Sparta in the 1960s. That’s what makes the confrontation between Tibbs and Endicott so powerful.

In the Heat of the Night also spawned one of the most famous lines of dialogue in movie history (the American Film Institute ranked it #16…it should have been higher). When Tibbs’ investigative skills expose a flaw in Gillespie’s initial theory about the crime, the following exchange take place:

Gillespie: Well, you're pretty sure of yourself, ain't you, Virgil? Virgil, that's a funny name for a nigger boy to come from Philadelphia. What do they call you up there?

Tibbs: They call me Mister Tibbs!

And that’s exactly what they called Virgil in two sequels in which Poitier reprised the role: They Call Me MISTER Tibbs (1970) and The Organization (1971). Sadly, neither film is very good. They transform Tibbs into a family man working in a big city—making him just another detective working the streets in a 1970s urban crime film.

In 1988, In the Heat of the Night was adapted as a television series starring Carroll O’Connor as Gillespie and Howard Rollins as Tibbs. Set in Sparta again, the show lasted for eight seasons, although Rollins was dropped after 1993 due to legal problems.

It took me years to watch this film. I wasn't avoiding it; it just took me a while to get to it. One morning, I turned on the TV before work, which I rarely do, and it'd just started. I could only watch 20 minutes, then had to go work (they demand attendance before signing the paycheck), but I DVR'ed it. That evening, I forgot all about it, but remembered it in the morning before work, etc. Basically, I watched it in pieces. But it's great! Nice post from Rick, and I love your blog, Kim!

ReplyDeleteSark, glad you like the blog...a number of your posts have made an appearance here! LOL!

ReplyDelete