The third installment in director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy, Red (1994), is by far the most philosophical and entertaining of the group. I am a fan of films that interconnect the seemingly unconnected—this is why I so adore directors/producers like Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and Alfonso Cuaron—and Three Colors: Red not only artfully pulls together what appears to be two independent stories but also seamlessly unites all three movies of the trilogy together in one fell swoop. Kieslowski was justly rewarded Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay (along with co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz) for his cinematic interpretation of the bonds of fraternity. How on earth this wasn’t one of the five nominees for Best Foreign Language Film is beyond comprehension (although if it had been nominated it wouldn’t have won, as even the film that should have won, Before the Rain, was somehow beaten by Burnt by the Sun—personally, I believe that international politics had a lot to do with this outcome…oh, s

Perhaps it is a coincidence that Red takes place in Geneva, Switzerland, but I like to believe Kieslowski chose this setting because of the Geneva Convention, which established the standards for the humanitarian treatment of war. No, this isn’t a movie about war, but it is, in some way at least, about how laws and society determine what is ethically and socially acceptable. As in the first two films of the trilogy, Red abounds with isolated, lonely characters. Valentine (Irene Jacob), a student, model, and pleasant and innately good person, is separated from her family and her pathologically jealous boyfriend. However, quite by accident, her world is changed by running over the dog of retired Judge Kern (Jean-Louis Trintignant). When she returns the dog to him, Kern seems not to care and she takes on the responsibility of nursing the dog back to health. When the dog runs away, Valentine returns to Kern’s house on the off chance that’s where the dog has gone. It also gives her a reason to return the excess amount of money that Kern sent to her to pay the dog’s vet bill. Of course, Kern knew that she

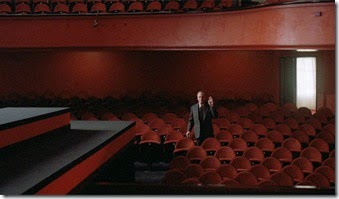

The twist to the plot is that there is a parallel story that runs throughout the movie that only starts to come together after Kern explains to Valentine (in an absolutely inspired setting: a dark red theater with red chairs) how he came to be such a wretched man. Like Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit), a young man studying for a judgeship (and the man who lives across the street from Valentine), Kern had dropped a jurisprudence book that when picked up was opened to a chapter which provided the answer to the most crucial question of the exam. And, as Auguste is deeply in love with a woman who betrays him (Frederique Feder), so was Kern. He was so desperately in love with her that he followed her across the English Channel but she died in an accident. Strangely enough, Auguste will follow his woman across the English Channel, too, but Valentine will also be on the ferry crossing. When a disastrous storm strikes, only

Red, of course, is the dominate color. It’s in every shot, either as an object, as a background, or as a lighting element. As mentioned above, perhaps the most striking use of the color is the set design of the theater. For me, Kern’s description of the events that destroyed his faith in man and in himself is deeply personal. He allows Valentine to see inside him—his metaphorical flesh--which is symbolically enveloped by the sea of red which encompasses the entire theater.

Obviously, I have droned on enough about why I prefer Red’s story arc to that of its trilogy mates, Blue (1993) and White (1994), but plot is not the only superior quality that Red has. Unequivocally, Red is the best acted of the three films. I‘m not trying to take anything away from Juliette Binoche’s turn in Blue, because she gives a haunting performance, but she didn’t have the luxury of working opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant. Unfortunately, American audiences, in general, have no idea who Irene Jacob is. Very early in her career she made two very important movies, Au revoir, les enfants (1987) and The Double Life of Veronique (1991), as well as Red, that found her poised for international stardom,

Overall, Red benefits from gorgeous cinematography, good acting, and a tightly-woven intricate story. If I were to levy a complaint about it, it would be that the idiotic phone conversations between Valentine and Michel (the jealous boyfriend) could have been cut without much notice.

No comments:

Post a Comment