Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Wednesday, June 24, 2015

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Monday, June 30, 2014

Seconds (1966) **1/2

Based on David Ely’s 1963 novel of the same name, Seconds (1966) is a disturbing science fiction—and, I would go as far as to say horror—film about a man who completely takes on a new identity to escape his meaningless suburban lifestyle. Director John Frankenheimer, along with cinematographer James Wong Howe, depicts a stark vision of a world where lives can be created or taken by an underground company headed by a man who looks and sounds a lot like Harry S. Truman (Will Geer). The story itself is so bizarre that it is frightening, and Howe’s voyeuristic cinematography and Jerry Goldsmith’s

On his nightly commute from his New York banking job to his suburban home in Scarsdale, Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) is given a scrap of paper with an address written on it. Later that evening he receives a phone call from a man claiming to be his dead best friend, Charlie (Murray Hamilton), who attempts to convince him to change his life. What happens next is a series of shockingly matter-of-fact conversations between Arthur and the “Company”. It seems that they can help him extricate himself from his empty existence, in which he no longer shares intimacy with his wife (Frances Reid), sees his married daughter, or enjoys his job. All he has to do is set up a trust worth $30,000 to handle his transition—a cadaver must be procured for his “death”; extensive plastic

![Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17] Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhhG9bN7nomlcpEZ0aO2M3NrT7NizQ-mWhW8_xV61ypBTuoL4QE5udEz1msZNxOgAdIA_Sxiu2HKhxy1dF0vE57pHBv2wkBUx_n5YDKVA0Vg5CbhJ2YxIcGLtichcE7zFsNqnMgM1eTflM/?imgmax=800)

Of course, such disturbing images deserved to be set to an equally disturbing soundtrack. While it has a sound all its own, Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack seems to pay homage to Bach’s Baroque style. Filled with imposing organs, melodic strings, and eerie 60s electronic music, the soundtrack is just as disquieting as the film’s subject matter.

Overall, while I must admit that the story is a bit far-fetched, it is also so disturbing that I couldn’t help but be drawn into it. It also helps that it was expertly filmed and that the soundtrack only enhanced the terror of the narrative.

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Blow-Up (1966) *

(There may be spoilers, if that’s possible, in this post.)

Somehow this 1966 film from famed Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni earned two Academy Award nominations: Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. Obviously drug abuse was a huge problem for Academy voters in the mid-60s, because Blow-Up is a really bad art film gone horribly wrong. I’m sure many a purist’s head is exploding as they read this, but I don’t care. For me, Blow-Up is painful to watch—sort of like another Antonioni movie, Zabriskie Point (1970), but only sligh

David Hemmings plays a famous London fashion photographer who spends his days surrounded by beautiful but vapid models and his nights taking vérité-esque pictures of men in flophouses (known as the doss house in England). The slight plot that there is comes about when the photographer happens upon a couple in a deserted park and starts taking photos of them. When the woman sees (Vanessa Redgrave) him she demands he give her the undeveloped film. Naturally he refuses—he thinks he wants to use the photos for the end of his upcoming book—and she shows up at his flat/studio and offers to sleep with him for the pictures. We never learn if this actually happens (like so many other things we never learn in this movie), but we do know that after she leaves he develops the film and discovers that she was attempting to hide the fact that she was part of a murder. Yes, I know this sounds like an interesting plot turn, but believe me, it’s not.

So, why didn’t I like this film? First, Blow-Up seems like a vanity project. Is the photographer a ‘complex’ and ‘conflicted’ representation of Antonioni himself, who makes inane films about rich and beautiful people but longs to do bigger things? Maybe, but again, I don’t care. Watching Hemmings drive around in a Rolls Royce and roll around on the floor with two dimwitted groupies was not must-see cinema. Rather, it seemed like a reflection of Antonioni himself and what he thought a successful artist should do to pass the time.

Finally, we must discuss the completely ridiculous ending (now is where ‘spoilers’ will appear). Did I watch a film for nearly two hours about an

Overall, it was bad---really bad. So many questions were left unanswered—and I’m not even talking about the film itself. The biggest question I find myself pondering is how the hell did Antonioni and fellow screenwriter Tonino Guerra’s screenplay for this get nominated for an Oscar? Was there really a script of insanely long periods of silence rewarded with such an honor? Are we sure it wasn’t an outline? Oh, the perils of “The Book”.

Monday, April 18, 2011

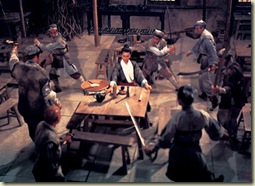

Come Drink with Me (Da Zui Xia) 1966 **

The protagonist of Come Drink With Me (1966) is a petite Chinese woman named Golden Swallow (Cheng Pei-pei…yes, the same lady from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). Based on this description, you might assume this is one of those Chinese teahouse stories where the main character is either a peasant or a princess who finds herself caught in a love triangle. You would be wrong, but at least you were right about their being a teahouse. No, Golden Swallow is a sword-wielding badass who likes to lure her adversaries into a false sense of security by sipping tea before she uses her two daggers to slice them up.

In addition, King Hu benefits from his other star, Yueh Hua, who plays Drunken Cat, a drunken beggar who assists Golden Swallow in her quest to free her brother, a

Though they have completely different personalities, Drunken Cat and Golden Swallow work well together. He serves as a wise advisor and capable accomplice. She’s a hothead who often acts before she thinks. It is through one of Drunken Cat’s opera songs that Golden

Come Drink With Me might not be the best martial arts film of all time, but it certainly is one of the most important. King Hu truly changed the Wuxi genre by